Sedimentary Basin Aquifers¶

Sedimentary basins aquifers are typically marked by primary (i.e. depositional opposed to secundary- e.g. due to fracturing) porosity and permeability.

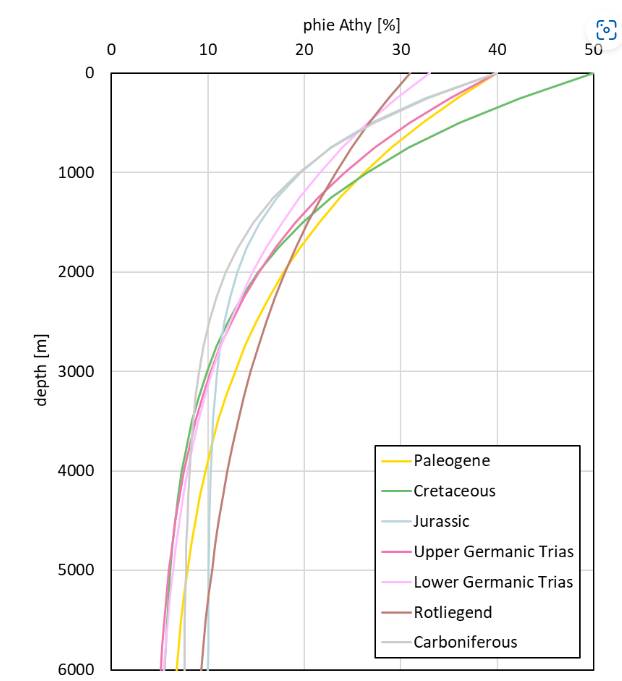

Basin analysis studies consistently show that porosity (and associated permeability) declines with (maximum) burial depth (Limberger et al.,2017).

Consequently an important trade-off is between higher temperatures with increasing depth, and declining flow rates due to declining porosity and permeability with depth.

In addition to primary porosity and permeability, secondary (porosity and) permeability can be present in sedimentary basins, which is typically related to diagenesis, such as dissolution, but also tectonics resulting in fracturing, and faulting. Fractured sedimentary rocks, in particular mechanically competent carbonate rocks can have high secondary (porosity and) permeability, which is succesfully exploited for geothermal energy production in many areas in Europe including the Paris Basin in France and the Molasse Basin in Germany.

Clastic reservoirs¶

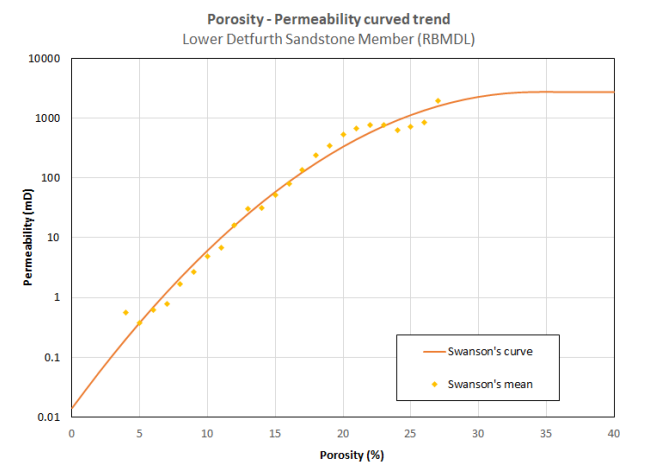

Clastic reservoirs comprise (unconsolidated) sandstone formations. In Clastic reservoirs grain size is positively related to porosity and permeability. In addition, from measurement in cores, as well as from theoretical considerations, a linear correlation exists between porosity and the natural logarithm of permeability (Pluymaekers et al., 2012; Vrijlandt et al., 2020).

For clastic (and formations basin analysis studies the mechanical compaction as function of burial depth is often described by the following equation (Limberger et al., 2017):

phiz = phi₀ - (phi₀ - phi₁) ∙ exp(- k z)

where:

- phiz is the porosity at depth z

- phi₀ is the porosity at the surface (z=0)

- phi₁ is the residual porosity at large depths (z → ∞), typically around 1-5%

- exp is the exponential function.

- k is athy's compaction coefficient, which is typically around 0.2-0.5 km⁻¹ for clastic reservoirs.

Figure 1: Porosity-depth relationships for Geothermal Clastic Aquifers in The Netherlands (Thermogis,2024)

Figure 2: porosity-permeability relationship for a Lower Germanic clastic aquifer (source Vrijlandt et al., 2020)

Carbonate reservoirs¶

Carbonate reservoirs are often marked by secondary permeability related to fractured rocks and dissolution features, which can be very high in some cases.

References¶

- Limberger, et al., 2017. A public domain model for 1D temperature and rheology construction in basement-sedimentary geothermal exploration: An application to the Spanish Central System and adjacent basins. Acta Geodaetica et Geophysica, DOI: 10.1007/s40328-017-0197-5*

- Pluymaekers, M., et al., 2012. Reservoir characterisation of aquifers for direct heat production: Methodology and screening of the potential reservoirs for the Netherlands. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences 91 (04): 621-636

- Van Wees et al., 2012. Geothermal aquifer performance assessment for direct heat production–Methodology and application to Rotliegend aquifers. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences, 91(4), 651-665. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600000433

- Vrijlandt, et al., 2020. ThermoGIS: from a Static to a Dynamic approach for National Geothermal Resource Information and Development, World Geothermal Congress 2020. https://www.geothermalenergy.org/pdf/IGAstandard/WGC/2020/16071.pdf